The Battle of the Atlantic was one of the most hard-fought campaigns of the Second World War.

The Battle of the Atlantic was one of the most hard-fought campaigns of the Second World War.America had not yet joined the war but Churchill had managed to persuade them to supply Britain's war effort on a loans basis to be re-paid after the war.

However, the supplies, once purchased, still had to be shipped to Britain by sea and this is what the convoys did. This was the vital lifeline after the Fall of France when Britain was isolated and alone against the might of Nazi Germany.

Whatever one may think of Winston Churchill, his stirring words continue to have a resonance today and are among some of the greatest of political speeches ever made in the English language. Who could ever forgot these famous words of 4 June 1940:

"We must never forget the solid assurances of sea power and those which belong to air power if they can be locally exercised. I have myself full confidence that if all do their duty and if the best arrangements are made, as they are being made, we shall prove ourselves once again able to defend our island home, ride out the storms of war and outlive the menace of tyranny, if necessary, for years, if necessary, alone.

At any rate, that is what we are going to try to do. That is the resolve of His Majesty's Government, every man of them. That is the will of Parliament and the nation. The British Empire and the French Republic, linked together in their cause and their need, will defend to the death their native soils, aiding each other like good comrades to the utmost of their strength, even though a large tract of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen, or may fall, into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule.

We shall not flag nor fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France and on the seas and oceans; we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air. We shall defend our island whatever the cost may be; we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, in the fields, in the streets and in the hills. We shall never surrender and even if, which I do not for one moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, will carry on the struggle until in God's good time the New World with all its power and might, sets forth to the rescue and liberation of the Old."

And he meant it, too!

So began the Atlantic convoys.

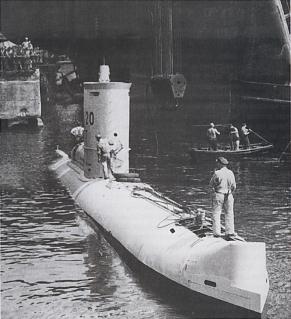

However, Nazi U-Boat technology and production was high and fairly soon they were able to hunt in "wolf-packs" to track down the convoys and torpedo them - often in the middle of the night in mid-Atlantic, miles from land and with the threat of imminent storms and dreadful seas. The courage required to face this threat was monumental.

Whilst the convoys were escorted by fighting ships of the Royal Navy, nevertheless it was they, the defenceless and unarmed convoys themselves, manned by sailors of the British Merchant Navy, that were most at risk of death by burning or a watery grave. For it was they whose ships contained the supplies for a blockaded Britain and who were thus the real prey for the U-Boat wolf-packs.

For this reason the men of the Royal Navy began to have the highest respect for the courage and tenacity of the merchant seamen who might at any minute find themselves blown to bits by a torpedo or cast into a freezing, swollen Atlantic swell, clinging to a piece of wreckage or perhaps a life-raft.

By 1942, most long-range bomber aircraft were being used for the ill-fated and morally questionable bombing campaign against German civilians (many of whom hated Hitler as much as the Allies). This, according to Professor Pat Blackett, the chief naval scientific adviser, exposed the convoys to ever greater risk. Blackett claimed this lengthened the war by as much as 6 months and possibly a whole year.

Casualties were very considerable and in the early stages many convoys suffered heavy losses. They continued to sustain heavy losses throughout the war but things began to improve as technology for detection of U-Boats improved.

By the spring of 1943, there were so many U-boats on patrol in the North Atlantic that it was difficult for the convoys to evade detection, resulting in a succession of high-loss convoy battles. In March the escorts were heavily defeated in the battles of convoys HX-228, SC-121, SC-122 and HX-229. 120 ships were sunk worldwide, 82 ships of 476,000 tons in the Atlantic, but only 12 U-boats were destroyed.

The supply situation in Britain was such that there was talk of being unable to continue the war effort, with supplies of fuel being particularly low. It appeared that Admiral Dönitz and his U-Boats were winning the war. And yet the next two months would see a complete reversal of fortunes.

In April, losses of U-boats increased whilst their kills of ships fell dramatically. 39 ships of 235,000 tons were sunk in the Atlantic, and 15 U-boats were destroyed.

By May, wolf packs no longer had the advantage and that month was to become known as Black May for the U-Boat Arm.

Faced with these reversals, Dönitz called off operations in the North Atlantic. In all, 43 U-boats were destroyed in May, 34 in the Atlantic. This was 25% of UbW’s total operational strength. The Allies lost 58 ships sunk in May, 34 ships of 134,000 tons were sunk in the Atlantic.

The tide had finally turned and Britain's supplies were now at last looking safer. Still, the risk for the Merchant seamen was very great and many a child of that era was taught, quite accurately, to be grateful for the food on their plates since many men had died bringing it to them. Hence the incredible thriftiness of that generation of men and women. Every scrap was used or preserved in gratitude and honour of the brave men who had risked all to bring it to British shores.

Many stories of collossal bravery are told of the sailors of that period, both officers and men.

Those who have seen the film The Cruel Sea will have had a taste of it. Every man was a brave one (with the possible exception of the First Lieutenant who finds an excuse to get a shore job early).

However, my particular favourite is the Coxswain who, albeit having at first to put up with the odious First Lieutenant, nevertheless maintains his placidity and discipline.

He is delighted that the Chief Engineer wants to marry his sister but they go ashore to find she has been killed in a bombing raid.

Later, when the ship is torpedoed and goes down, he has occasion to rebuke a seaman who has, contrary to regulations, gone overboard without his life-vest. The Coxswain then gives up his place in the life-raft and says he will swim to the other life-raft. "It's not far off", says he, not really knowing how far off it is and doubtless realising that he is risking his own life for another. In the darkness of the night he never makes it, is lost and never seen again.

Who can fathom the bravery of men like this?

And yet there were many of them - hundreds even. Men of the highest courage and nobility in whose shadow the rest of us can but live.

I was an officer myself in the Army but I take my hat off to the men of the Merchant Navy and not least to the ordinary seaman and NCOs who exhibited discipline, selflessness and courage of this sort.

"Greater love than this no man hath, that he lay down his life for his friends" [John 15:13]

The SS City of Benares was part of convoy OB-213, carrying 90 child evacuee passengers from wartime Britain to Canada. She departed Liverpool on 13 September 1940, bound for the Canadian ports of Quebec and Montreal.

At 00.01 hours on 18 September, U-48 torpedoed her, causing her to sink within 30 minutes, 253 miles west-southwest of Rockall.

15 minutes after the torpedo hit, the vessel had been abandoned, though there were difficulties with lowering the lifeboats on the weather side of the ship. HMS Hurricane arrived on the scene 24 hours later, and picked up 105 survivors and landed them at Greenock in Scotland. During the attack on the SS City of Benares, the SS Marina was also torpedoed. Hurricane mistakenly counted one of the lifeboats from the SS Marina for one of the lifeboats from SS City of Benares.

As a result, Lifeboat 12 was left alone at sea.

Its passengers had three weeks supply of food, but enough water only for one week. In the lifeboat were approximately 30 Indian crewmen, a Polish merchant, several sailors, Mary Cornish the concert pianist, Father Rory O'Sullivan (a Roman Catholic priest who had volunteered to be an escort for the evacuee children), and 6 evacuee boys. They spent 8 days afloat in the Atlantic Ocean before being sighted from the air and rescued by HMS Anthony.

In total, 248 of the 406 people on board, including the master, the commodore, three staff members, 121 crew members and 134 passengers were lost. 77 of the 90 child evacuee passengers were also killed in the sinking and only 7 children survived in total.

Fr O’Sullivan survived to live on until his 98th year in 2007, refusing to the last to go into any kind of nursing home.

Tales of heroic valour were later told of those on the boat. One young Ordinand kept 2 children above the water, hoping to save them as he slowly froze. Eventually he died of exposure as, alas, did the 2 children, though he had done his best to save them.

The thought of this brave young man risking all in the apparently - and indeed actually - hopeless task of saving 2 children is a story of the most inspiring and noble kind. Giants of courage then walked the earth. Shall we see their like again?

One can but recall the words of Scripture telling us that at the end of time:

"And the sea gave up the dead that were in it" [Apoc 20:11]

How many, then, brave men and women shall we see rising from their seabed graves to the glory of heaven ahead and above us lesser mortals!

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who biddest the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who biddest the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

...

.jpg)

_-002.jpg/220px-Circle_of_Anton_Raphael_Mengs,_Henry_Benedict_Maria_Clement_Stuart,_Cardinal_York_(ca_1750)_-002.jpg)

2 comments:

Excellent post, and thank you. I share your sentiments regarding the too-often-neglected merchant navies of both the US and the UK.

To be pedantic, though, the flag illustrating your post isn't the one the British merchant navy sailed under in world war two, and in fact hasn't been in use since 1800, when St Patrick's Cross was added to represent Ireland. But maybe you knew that.

Anyway, the current red ensign can be seen here.

Well spotted, sir!

I had only just seen it myself since it was, of course, the flag of the Stuart monarchs when, as you rightly say, the flag of St Patrick had yet to be added!

Go to the top of the class!

Tribunus

Post a Comment