I think he is worth quoting:

"The Latin of the Vulgate is not a vernacular in any sense. Send your correspondent to read Fr Uwe Michael Lang. It is called the 'Latin Vulgate' as it is the counterpart of the 'Greek Vulgate', it has NOTHING to do with vernacular; the language of the scriptural and liturgical Latin is legal and literary, not populist".

So there you have it, Miss Anglo-Catholic; and, indeed, vernacular-obsessed modern Catholics, too.

In fact, of course, the Hebrew, Greek and Latin languages are important to us because they are the languages of revelation, not because they are vernacular languages. they gave us the Old Testament (Hebrew), the New Testament (Greek) and the language of the Church's teaching and law inspired by the Holy Ghost (Latin), corresponding to Father, Son and Holy Ghost, respectively.

Sorry, Miss Anglo-Catholic, English is simply not one of the languages of revelation.

Get used to it.

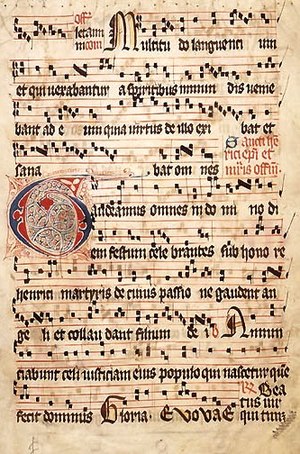

St Jerome, translator of the Bible into Latin, in his Scriptorium, shown here in a stylized medieval portrait

St Jerome, translator of the Bible into Latin, in his Scriptorium, shown here in a stylized medieval portrait

Eusebius Hieronymus Sophronius, better known as St Jerome, was born sometime between 340 and 347 AD in Stridon, a town on the border between the Roman provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia (now on the Italian side of the modern Italian-Croatian border).

He received a classical education and was tutored in Rome by the grammarian Donatus. At age eighteen he was baptized in Rome by Pope Liberius. He was well read in the Pagan poets and writers.

Jerome traveled extensively throughout the Roman Empire. He began formal theological studies in Trier. He moved to Aquileia in 370, where he met St Valerian. About 373 he headed to the East.

From 374 to 379 Jerome led an ascetic life in the desert southwest of Antioch. During this period he heard Apollinaris of Laodicea, a leading Bible scholar, who later left the Church. In 379, he was ordained a priest at Antioch by St Paulinus.

Jerome went to Constantinople about 380 to study scripture under St Gregory Nazianzus. In 382 he returned to Rome, where he became secretary to Pope Damasus who suggested that he revise the translations of the Gospels and the Psalms.

When Damasus died in 384, Jerome had to leave Rome, because his outspoken, often harsh criticism of Roman society created enemies. His travels returned him to Antioch, then to Alexandria, and finally to Bethlehem in 386, where he settled in a monastery.

There he translated the Old and New Testaments into Latin. This translation was recognized eleven centuries later by the Council of Trent as the official version of the Bible: the Vulgate.

In 410 Rome came under attack by the barbarian Alaric, creating numerous refugees who sought safety in the Holy Land. In the interest of providing for them Jerome wrote, "I have put aside all my study to help them. Now we must translate the words of Scripture into deeds, and instead of speaking holy words we must do them."

St Jerome died at Bethlehem from a long illness on 30 September 420.

He is buried in the Basilica of St Mary Major in Rome.

...

.jpg)

_-002.jpg/220px-Circle_of_Anton_Raphael_Mengs,_Henry_Benedict_Maria_Clement_Stuart,_Cardinal_York_(ca_1750)_-002.jpg)

36 comments:

The phrase "language of revelation" when applied to Latin is a curious one. Roman Catholics and members of "mainstream" denominations (though not Mohammedans or Mormons, for example) believe that God's Revelation to His People culminated with His Revelation of Himself in Jesus Christ, and thus that Revelation came to an end with the death of the last Apostle. To say that Latin is a language of revelation because Latin became the official language of the Catholic Church (and by extension because the Scriptures were translated into Latin) is a circular argument.

It is always advisable for a scholar to cite his sources.

Jerome's work fell into five main categories: biblical analysis, theological debate, history, correspondence, and of course translation.

His earliest translation subjects (379-81) included the homilies of Origen on Jeremias, Ezechiel, and Isaias and the Chronicle of Eusebius. But he earned his place in history mainly from his translations and revisions of the Bible. Originally he believed the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew scriptures into Greek several centuries B.C.E., to be divinely inspired. However, his continuing study of Hebrew and discussions with rabbis convinced him that only the original text was inspired. This led to his decision to undertake a new translation of the Old Testament.

This new translation drew chiefly upon Hebrew texts in current use, whereas the Septuagint was translated from an older Hebrew version, presumably more authentic. Modern critics cite this neglect of the older text as a shortcoming, especially compared to the general excellence of Jerome's translation work.

Unduly catty, aren't we, Glorfindel?

The substance of my post is not to bandy citations about the history of Jerome (which is not disupted) but rather to quote a correspondent's view that the Vulgate is not vulgar.

You might as well ask me to cite the source of every picture image that I use - something which I note that you do not do.

"Do as you would be done by" is our guide, Glorfindel, is it not?

I do not think it is too long a bow to call Latin a language of revelation and it is certainly not, as you rather randomly suggest, a "circular argument". Indeed, it is not an "argument" at all.

Latin is the language in which Revelation (with a capital "R") has been explained to the Church through the decrees of popes and councils and, in that sense, is a language of revelation.

Not all revelations are Revelation.

Miaow, pussycat.

Flattered, Tribunus!

"The Catholic Church uses Latin because Latin is a language of revelation."

"Latin is a language of revelation because it is the language of the Catholic Church."

This is a circular argument.

Thanks to you, Josephus for the information!

Glorfindel,

You might be right if that were the sum of my argument but it is clear to anyone without an axe to grind - which alas excludes you - that your caricature is not my argument but only a creature of your rather quirky prejudices.

Wrong about Gin Lane, wrong about the languages of revelation; have you something positive to contribute to this discussion, Glorfindel?

We can but hope...

Given that the phrase "language of revelation" is an invention of the current writer, it is clearly his prerogative to say what this phrase does and does not mean. It would perhaps have been more honest for the writer to have written that he calls Latin a language of revelation.

Hogarth's Gin Lane was an attack on drunkeness, not poverty per se. The logic of its argument is that moral degeneracy (in this case drunkeness) leads to poverty (and other social evils), not the other way around. (There is a brief discussion about the causes of poverty and its connexion with moral degeneracy in the article on poverty and pauperism in the Catholic Enclyclopedia.) There is very little evidence that Hogarth was attacking Protestantism, much less that this was his intention.

Your argument does not improve by mere repetition after its rebuttal.

The primary invention, here, is your mis-description of my claims about the importance of Latin.

No-one, except perhaps you, denies that the Latin language, as the official language of the Church, is the language in which the Church reveals and explains to the Faithful what is meant by Revelation (capital "R") contained in the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament.

That, as such, is why it is a language of far greater importance for Catholic teaching than, say, English or Sanskrit.

It is the language in which the Church teaches us about Revelation (capital "R").

Rather than admit this you prefer to miss the wood for a tree of pedantry of your own making.

Well, it's a point of view.

I shan't rehearse again the arguments over Hogarth's Gin Lane which are available in my earlier post and which you signally failed to answer.

Now you tilt at new windmills averring that Hogarth's painting purports to show that gin led to poverty and that he was not, and did not, intend to attack Protestantism.

Very interesting but I have argued neither.

I reported a common scholarly view (sources previously cited) that Hogarth was attacking a society that allowed such poverty.

It is difficult to escape the view that you have moved on from serious enquiry and are resorting, instead, to mere sour grapes (capital "S", perhaps?).

Latin is clearly not a language of revelation, except in the very vague sense that Latin is the official language of the Catholic Church. In this sense, the writer's contention may be accepted as correct.

The writer is correct in his contention that the Latin of the Vulgate 'is not the vernacular', but only in the sense that the Vulgate was not written in "vernacular Latin". As the Catholic Encyclopedia explains,

Classical Latin did not long remain at the high level to which Cicero had raised it. The aristocracy, who alone spoke it, were decimated by proscription and civil war, and the families who rose in turn to social position were mainly of plebeian or foreign extraction, and in any case unaccustomed to the delicacy of the literary language. Thus the decadence of classical Latin began with the age of Augustus, and went on more rapidly as that age receded. As it forgot the classical distinction between the language of prose and that of poetry, literary Latin, spoken or written, began to borrow more and more freely from the popular speech. Now it was at this very time that the Church found herself called on to construct a Latin of her own and this in itself was one reason why her Latin should differ from the classical. There were two other reasons however: first of all the Gospel had to be spread by preaching, that is, by the spoken word moreover the heralds of the good tidings had to construct an idiom that would appeal, not alone to the literary classes, but to the whole people. Seeing that they sought to win the masses to the Faith, they had to come down to their level and employ a speech that was familiar to their listeners. St. Augustine says this very frankly to his hearers: "I often employ", he says, "words that are not Latin and I do so that you may understand me. Better that I should incur the blame of the grammarians than not be understood by the people" (In Psal. cxxxviii, 90). Strange though it may seem, it was not at Rome that the building up of ecclesiastical Latin began. Until the middle of the third century the Christian community at Rome was in the main a Greek speaking one. The Liturgy was celebrated in Greek, and the apologists and theologians wrote in Greek until the time of St. Hippolytus, who died in 235. It was much the same in Gaul at Lyons and at Vienne, at all events until after the days of St. Irenæus. In Africa, Greek was the chosen language of the clerics, to begin with, but Latin was the more familiar speech for the majority of the faithful, and it must have soon taken the lead in the Church, since Tertullian, who wrote some of his earlier works in Greek, ended by employing Latin only. And in this use he had been preceded by Pope Victor, who was also an African, and who, as St. Jerome assures, was the earliest Christian writer in the Latin language.

But even before these writers various local Churches must have seen the necessity of rendering into Latin the texts of the Old and New Testaments, the reading of which formed a main portion of the Liturgy. This necessity arose as soon as the Latin speaking faithful became numerous, and in all likelihood it was felt first in Africa. For a time improvised oral translations sufficed, but soon written translations were required. Such translations multiplied.

The writer's contention appears to be that Protestantism in England caused poverty and that Hogarth's print Gin Lane may be adduced as evidence of this. The truth is that Hogarth's Gin Lane was a work of political propaganda attacking drunkeness - specifically caused by drinking gin (rather than beer). It was not an attack on poverty per se, much less an attack on any particular sort of poverty caused by Protestantism.

I find it very puzzling to be told that the Latin of the Vulgate is the official language of law and government. Anyone with a nodding acquaintance with classical Latin has but to pick up a Vulgate to discover that its language is less inflected, full of peculiar idioms, sui generis, in fact. This is particularly obvious in the New Testament which was not re-translated, but merely lightly revised and standardized, by St. Jerome.

Some of that oddity comes from the fact that the Latin used there is a more simplified and popular variety of Latin than, say, Cicero. Some of it is due to a literalistic approach to the Koine Greek of the New Testament.

Perhaps it is better to say that Latin is a language of inspiration. Joseph Ratzinger believes that the traditional liturgy of the Church is inspired as is Scripture. I get the idea you are trying for but I do think the wording is a bit faulty.

The Holy Ghost works in the Church over time, guiding and assisting in its growth and hallowing the forms of worship and prayer that take form in the bosom of the Church. The Latin Vulgate is not simply a "translation" in that sense, it is hallowed as all tradition is, but in a special sense too.

And the Latin language too grew and developed over the centuries under the guidance of the Holy Spirit It embodied and ennobled, as it was ennobled by, Christ's continuing work in the Church, His Body.

This future was adumbrated by its appearance as one of the three languages of the Cross. It was no accident that the Gospel appeared and the Church was born in a Hebrew corner of a Greek region of a Latin Empire.

The writer's contention does not merely “appear” to be that Protestantism in England caused poverty – it is clearly stated to be my opinion.

I wrote:

“The common people were never so persecuted, hunted, harried, down-trodden, ill-educated, starved, beaten and mercilessly oppressed as they were after the Protestant Reformation, as Cobbett amply proves.”

And this:

"The Protestant Reformation reduced the common people of England to extreme poverty and, often enough, utter destitution and degradation as Hogarth so well illustrated".

What could be clearer?

In support I cited Cobbett, Dickens and Ronald Paulsen.

You have rebutted neither and you cite no other sources except to repeat your own unsupported opinion. Re-statement is not proof.

Here is what Cobbett in his Protestant Reformation says:

“331 Returning now to paragraphs 50, 51, 52 just mentioned, it is there seen that the Church rendered all municipal laws for the poor wholly unnecessary but when the Church had been plundered and destroyed the greedy leading Reformers had sacked the convents and the churches, when those great estates which of right belonged to the poorer classes had been taken from them, when the parsonages had been first well pillaged and the remnant of their revenues given to married men then the poor - for poor there will and must be in every community – were left destitute of the means of existence other than the fruits of begging theft and robbery. Accordingly when good Queen Bess had put the finishing hand to the plundering of the Church and poor, once happy and free and hospitable England became a den of famishing robbers and slaves.”

And later:

“Surely enough, the Reformation has led to our then present and our now present situation. It has at last produced the bitter fruit of which we are now tasting. Evidence given by a clergyman, too, and published by the House of Commons in 1824 states the labouring people of Suffolk to be a nest of robbers too deeply corrupted ever to be reclaimed. Evidence of a Sheriff of Wiltshire in 1821 states the common food of the labourers in the field to be cold potatoes. A scale published by the magistrates of Norfolk in 1825 allows 3d a day to a single labouring man. The Judges of the Court of King's Bench in 1825 have declared the general food of the labouring people to be bread and water. Intelligence from the counties in 1826, published upon the spot, informs us that great numbers of people are nearly starving and that some are eating flesh and grains while it is well known the country abounds in food, and, while clergy have recently put up from the pulpit rubrical thanksgiving for times of plenty, a law recently passed making it felony to take apple from a tree tells the world that our characters and lives are thought nothing worth, and that this nation, once the greatest and most moral in the world, is now a nation of incorrigible thieves, and, in either case, the most impoverished, the most fallen, the most degraded, that ever saw the light of the sun.”

Even though he actually lived at the time, perhaps you think you know better than he?

Your extract regarding Church Latin is from the CE article written by Antoine Dégert who was well-known for being a vernacularist.

You would be better taking a far higher authority as your guide, namely the Holy See.

Here is what Blessed Pope John XXIII taught on the importance of Latin in his Apostolic Constitution Veterum Sapientia:

“The wisdom of the ancient world, enshrined in Greek and Roman literature, and the truly memorable teaching of ancient peoples, served, surely, to herald the dawn of that gospel which God's Son, 'the judge and teacher of grace and truth, the light and guide of the human race,' proclaimed on earth. Such, at any rate, was the view of the Church's Fathers and Doctors. In these outstanding literary monuments of antiquity they recognized man's spiritual preparation for the supernatural riches which Jesus Christ communicated to mankind 'to give history its fulfilment'... The Church has ever held the literary evidences of this wisdom in the highest esteem. She values especially the Greek and Latin languages, in which wisdom itself is cloaked, as it were, in a vesture of gold... But amid this variety of languages a primary place must surely be given to that language which had its origins in Latium and later proved so admirable a means for the spreading of Christianity throughout the West. And since in God's special providence this language united so many nations together under the authority of the Roman Empire - and that for so many centuries - it also became the rightful language of the Apostolic See. It was thus preserved for posterity and was instrumental in joining the Christian peoples of Europe together in the close bonds of unity. Of its very nature Latin is most suitable for promoting every form of culture among peoples... For these reasons the Apostolic See has always been at pains to preserve Latin, deeming it worthy of being used in the exercise of her teaching authority 'as the splendid vesture of her heavenly doctrine and sacred laws'... Thus the 'knowledge and use of this language', so intimately bound up with the Church's life, 'is important not so much on cultural or literary grounds as for religious reasons'. These are the words of Our Predecessor, Pius XI, who conducted a scientific enquiry into this whole subject and indicated three qualities of the Latin language which harmonize to a remarkable degree with the Church's nature.

[cont]

'For the Church, precisely because it embraces all nations and is destined to endure until the end of time ... of its very nature requires a language which is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular'. Since 'every Church must assemble round the Roman Church,' and since the Supreme Pontiffs have 'true episcopal power, ordinary and immediate, over each and every Church and over each and every Pastor, as well as over the faithful' of every rite and every language, it seems particularly desirable that the instrument of mutual communication be uniform and universal, especially between the Apostolic See and the Churches which use the same Latin rite. When, therefore, the Roman Pontiffs wish to instruct the Catholic world, or the Congregations of the Roman Curia handle affairs or draw up decrees which concern the whole body of the faithful, they invariably make use of Latin, for this is the 'mother tongue' acceptable to countless nations. Furthermore, the Church's language must be not only universal but also immutable. Modern languages are liable to change, and no single one of them is superior to the others in authority. Thus if the truths of the Catholic Church were entrusted to an unspecified number of them, the meaning of these truths, varied as they are, would not be manifested to everyone with sufficient clarity and precision. There would, moreover, be no language that could serve as a common and constant norm by which to gauge the exact meaning of other renderings. But Latin is indeed such a language. It is set and unchanging... Finally, the Catholic Church has a dignity far surpassing that of every merely human society, for it was founded by Christ the Lord. It is altogether fitting, therefore, that the language it uses should be noble and majestic, and non-vernacular. In addition, the Latin language 'can be called truly Catholic'. It has been consecrated through constant use by the Apostolic See, the mother and teacher of all Churches, and must be esteemed the treasure . . . of incomparable worth'. It is a general passport to the proper understanding of the Christian writers of antiquity and the documents of the Church's teaching. It is also a most effective bond, binding the Church of today with that of the past and of the future in wonderful continuity... It will be quite clear from these considerations why the Roman Pontiffs have so often extolled the excellence and importance of Latin, and why they have prescribed its study and use by the secular and regular clergy, forecasting the dangers that would result from its neglect...”.

Hardly a “vague sense”, I suggest!

Thanks, Jeff. Indeed, I agree.

And I am content to join you in calling it a language of "inspiration" given that my original post, in passing (since that was not the main issue), pointed to Latin as one of the three prime sacred languages.

Unfortunately, Glorfindel has chosen, instead, to take it as an opportunity to split hairs in an unhelpfully pedantic and ultimately futile way.

No doubt he/she will now imagine that your use of the term "inspiration" is the whole sum of what you are trying to say and call it circular to say that Latin is the language of inpiration because it later became the official language in which the Church taught and legislated (by inspiration), or some such other non-sequitur that advances the Gospel not a whit.

The writer dismisses the Catholic Encyclopedia as "vernacularist".

Seemingly without irony, he then invokes no less an authority than the Pope who convened the Second Vatican Council.

Hogarth's print Gin Lane is not evidence of poverty in Protestant England. Hogarth's famous print was a work of political and specifically Protestant (Puritanical, English nationalist) propaganda. It was not even attacking poverty per se, so much as the moral degeneracy caused by strong drink.

Dickens's works attacking poverty were similarly satyric. Oliver Twist, arguably Dickens's "break through" work, started out as an attack on the New Poor Law of 1834, which was intended to combat pauperism.

William Cobbett was a radical who supported the Reform Bill of 1832.

It is an especially poor sort of argument to attack a writer for his motives rather than reading and considering what he actually had to say.

One author of an article is not the whole Catholic Encyclopaedia.

Moreover, you may not have noticed that the Catholic Encyclopaedia is not infallible.

On the other hand, the Pope, even the Pope who called the Vatican Council, is infallible in his teaching.

Moreover, if you think Blessed John XXIII was some sort of flaky liberal then you know very little about him.

If you think that Dickens was only joking when he attacked the poverty of 19th century England then you will be in an even smaller minority than the number of people who think that the Benthamite Poor Law of 1832 actually helped the poor rather than persecuting them yet more.

Well done in identifying Cobbett as a radical. Unfortunately for your interpretation, in 1832 a radical meant a Jacobite-like radical conservative.

No-one has ever seriously contested Cobbett's account of the Protestant Reformation since it was based upon Lingard's widely respected History.

Gin Lane is not about poverty because, er, poverty is not what it's about.

Oh, right, Glorfindel.

Highly persuasive argument.

Well done.

I accept your admission that you have now run out of arguments.

The Pope is infallible when he defines matters of faith and morals. It is quite possible for different Popes to have different opinions about church history and the liturgy.

Blessed John XIII presided over the First Session of Vatican II, when the Council voted for the vernacular.

Cobbett was a radical in the sense that he supported freedom and democracy rather than oligarchy and the status quo. His historical revisionism should perhaps be considered in light of his support for Catholic emancipation.

The Poor Laws were intended to combat pauperism, not poverty. They were very successful. Dickens hated them because he was a liberal. That is why he satirised them.

Gin Lane was about gin. The clue is in the title. If it had been about poverty Hogarth would have called it Poverty Lane.

The Pope is indeed infallible when he defines matters of faith and morals; but the Catholic Encyclopaedia is not infallible. Not now and not ever.

Blessed John XIII did indeed preside over the First Session of Vatican II but the Council never "voted for the vernacular", if by that you mean "replaced and removed Latin".

Read Sacrosanctum Concilium and you will enjoy a voyage of discovery: at no stage did it mandate the vernacular and, indeed, only permitted it exceptionally. The Council decreed, moreover:

"Particular law remaining in force, the use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites".

You give your own definition to the word "radical" and thus do the very thing you complained of in my use of the word "revelation".

Pots and kettles?

Cobbett was a radical in the sense that he was not a Whig or a Tory but a supporter of the pre-Reformation Constitution of England, not merely a supporter of "freedom and democracy". Everyone claims to be a supporter of "freedom and democracy" so that is not much of a distinction.

His support for Catholic emancipation should be considered in the light of his historical views - not vice versa.

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 was the Act that resulted in the widespread use of workhouses which separated families and degraded the poor in the manner so successfully and savagely attacked by authors like Dickens who was certainly no liberal in the modern sense.

It was a characteristic of the gross hypocrisy of the Benthamite framers of these laws to make artificial distinctions between "pauperism" and "poverty". If justice and humanity to the poor represent success, the Act was grossly unsuccessful.

Gin Lane was about poverty as much as gin. No "clues" are needed but rather opinions from respectable academic and learned sources. I provide some. You provide none.

Anyone who thinks that painters and artists title their works only by bluntly obvious names has little idea about either art or artists.

The vernacular was introduced at Vatican II with the intention of helping people to understand the liturgy. It was part of an agenda that actually predated Blessed John XXIII, but he and the Council Fathers went along with it.

Cobbett was not a Catholic himself. That his support for Catholic emancipation was purely political can be easily seen. He supported an extension of freedom and democracy over the comparatively oligarchic status quo. The Reform Bill of 1832 did not restore the pre-Reformation Constitution of England. Instead it secured the political legacy of the Industrial Revolution.

In a legal and technical sense, pauperism denotes the condition of persons who are supported at public expense, whether within or outside of almshouses. More commonly the term is applied to all persons whose existence is dependent for any considerable period upon charitable assistance, whether this assistance be public or private.

This difference between pauperism and mere poverty is a significant one. The above quotation is from the Catholic Enclyclopedia, whose article on the subject is well worth reading. For a more modern discussion of these issues a good, readable polemic is James Bartholomew's book The Welfare State We're In. Charles Dickens's political sympathies can easily be discerned from the opening chapters of Oliver Twist.

There is no evidence that Gin Lane was anything other than an attack on drunkeness caused by "foreign" gin - with the implication that it leads to social decay and moral degeneracy. Its meaning is perfectly plain. For all his faults and virtues, as a satirist Hogarth could never conceivably be accused of subtlety.

Your comments on the vernacular add nothing to this debate and do not rebut anything I have said. It is quite clear that Blessed Pope John XXIII intended Latin to be the norm.

It was I who told you that Cobbett was an Anglican.

He did not merely support Catholic emancipation. That his support went very much further than the political can be seen from his book Reformation which I have now recommended to you several times and which it is clear that you have chosen to ignore because it so clearly demolished your thesis - a thesis for which you have provided no evidence beyond your own unsupported opinion.

Why, exactly, you wish so dishonestly to abuse the memory of Cobbett, is less clear.

No-one has suggested - least of all me - that The Reform Bill of 1832 restored the pre-Reformation Constitution of England. It would be an absurd claim. You might as well say that it made the moon go backwards.

On the other hand, it certainly did not "secure the political legacy of the Industrial Revolution" which was largely a legacy of Capitalist exploitation of the poor.

Numerous dictionaries define "Pauperism" as:

"the state or condition of utter poverty. Also called pauperage".

The fact that the Poor Law made a distinction between "pauper" and "destitute" makes no difference to this debate.

James Bartholomew's book The Welfare State We're In is a good study.

However, I am not sure how it supports your view about Charles Dickens', Cobbett's or Hogarth's political sympathies.

One does not need to read the opening chapters of Oliver Twist to now that Dickens was no great believer in the Workhouse system brought in by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834.

But since he was thus, I do not see but that you have done any more than prove my point.

In your rather pedantic terms, he considered both pauperism and poverty to be great scourges in 18th and 19th century England.

His view, and that of Paulsen, is but some of the evidence that shows that Hogarth's Gin Lane was far more than just an attack on "foreign" gin.

You may repeat until you begin to spin that its meaning is perfectly plainly only what you say it is but your own unsupported view is hardly evidence.

Hogarth did not need to be subtle in order to demonstrate poverty in the England of his day.

Blessed John XXIII probably did intend Latin to be the norm, at least for the Ordinary of the Mass. Nevertheless, he went along with a limited introduction of the vernacular into the liturgy in order to help people to understand it better.

The Reform Act of 1832 granted seats in the House of Commons to large cities that had sprung up during the Industrial Revolution, and took away seats from the so-called "rotten boroughs". Cobbett supported it.

Nothing dishonest or abusive of the memory of William Cobbett has been written here.

For the word 'pauper' The Concise Oxford Dictionary gives '1. a person without means; a beggar. 2. hist. a recipient of poor-law relief'. It was pauperism in this latter sense that the Poor Law reform of the 1830s was intended to deal, with quite a degree of success.

Bartholomew's book deals with the Poor Law amendments of the 1830s on pages 31 to 38 of the 2004 edition. His contention, that it was the effective abolition herewith of Elizabeth Tudor's Poor Law regime of 1601 that led to the emergence of "Victorian virtues", is cogently argued. Charles Dickens - himself an adulterer as well as a purveyor, in Trollope's words, of "popular sentiment" - was opposed to the new regime.

All of Hogarth's most famous works were moral works, including A Harlot's Progress and A Rake's Progress, Marriage à-la-mode, and Industry and Idleness. Gin Lane is very clearly in this tradition, attacking alcoholism just as his previous works had attacked debauchery, greed and sloth, and so on. To claim that Hogarth was somehow attacking poverty per se is to miss the moral point he was making.

Glorfindel, I think we are coming to the end of this discussion.

You are saying little or nothing new and merely repeating yourself and relying upon yourself as your own authority which is interesting coming from someone who claims to know what is "advisable for a scholar".

Blessed John XXIII did not "probably" intend Latin to be the norm, he clearly decreed it so in Veterum Sapientia and by no means just for the Ordinary of the Mass.

It is doubtful that he even intended the readings to be normally in the vernacular.

Your previous email aimed at the idea that the Reform Bill of 1832 restored the pre-Reformation Constitution of England. It was both irrelevant to the discussion and an absurd claim which no-one was making.

What your write now does nothing to address that point but - once again - goes off at an entirely irrelevant tangent.

Try to stick the issue (if you can).

That the Reform Act of 1832 granted seats in the House of Commons to cities that had sprung up during the Industrial Revolution, does not support the assertion that it "secured the political legacy of the Industrial Revolution" since that legacy was largely a legacy of Capitalist exploitation of the poor, not new seats for new cities.

Your claim that Cobbett's support for Catholic emancipation was purely political, and easily so seen, was not only a false claim it was also, given Cobbett's true views on the issue, dishonest and abusive, not only of him personally but also of the true historical facts.

You now agree with me on the meaning of the word "pauper" I am pleased to see.

On the other hand if you think it "successful" for a "recipient of poor-law relief" to be separated, by the 1834 Act, from his or her family and set to work in an odious workhouse, of which there were later many, then I must assume that you approve of the more unpleasant forms of exploitation of the poor and have no time for Catholic Social teaching.

Anyone seriously contending that it was the abolition of Elizabeth Tudor's Poor Law regime of 1601 that led to the emergence of "Victorian virtues", has perilously little idea of what a cogent argument is.

Indeed, anyone who thinks that a mere statute can generate "virtues" is living in a world of self-delusion.

The truth of the matter is that the Reformation was a catastrophic disaster for the English poor and created a whole new class of paupers and beggars and demolished the highly successful system of private welfare, health and education which had been provided by the monasteries, whose resources was wolfed by the new rich.

Henry VIII simply hanged beggars and let the poor starve and for many years there were no effective hospitals in operation.

Elizabeth's government was obliged to introduce a poor law which was like papering over a very large crack.

The 1834 Act was little better since it also penalised the poor for being poor, whether they were responsible for it or not.

The workhouse regime became a national disgrace in many parts of the country and the values that were often inculcated were those of Dotheboys Hall rather than of the ancient hospitality of the monasteries.

Moreover, since I perceive that you are an economic libertarian, it is a simple fact that the workhouse system was a government run system whereas the system of monastic welfare was an entirely private, non-state system.

Growing state welfare became an inevitable consequence of the Protestant Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries.

The Roman Catholic monasteries provided the greatest form of private social welfare that the world has ever seen. There has never any to equal them, before or since.

For entirely selfish reasons, King Henry VIII and his odious new Protestant men made a smash and grab raid on this great patrimony of the poor to line their own pockets.

Both you and Batholomew evidently overlook these facts.

If you think that by merely calling Charles Dickens an adulterer you satisfactorily proved that his criticism of poverty in England lacks all value then, once again, you are wide of a cogent argument.

All of Hogarth's most famous works were indeed moral works. The problem is that you do not seem to see poverty as a moral issue and so cannot see that Hogarth might be attacking it on that basis.

Thus, if anyone is missing the moral point, it is you.

The main effect of the Industrial Revolution was urbanisation. The Reform Bill of 1832 gave the new industrial towns political recognition. This is what the radicals of the day, including Cobbett, wanted. If Cobbett had wanted to restore the pre-Reformation Constitution of England he would not have supported this sort of progressive legislation.

Cobbett was an Anglican. If his interest in Catholicism had been genuine, rather than political, he would have become a Catholic himself. There is nothing either dishonest or abusive of his memory in this.

For the word 'pauper' The Concise Oxford Dictionary gives '1. a person without means; a beggar. 2. hist. a recipient of poor-law relief'. It was pauperism in this latter sense that the Poor Law reforms of the 1830s was intended to deal.

James Bartholomew's book The Welfare State We're In is a good study of these Poor Law reforms. They did not exploit the poor, nor did they separate people from their families. They certainly did not penalise people for being poor. On the contrary, they were very successful in combating pauperism. Conditions in the workhouses, which had already been in existence for a long time, were deliberately made harsher in order to discourage dependency. But people were not forced into the workhouses and they were free to leave them and take up paid employment outside them whenever they wished.

There is a good, non-polemical site on the English workhouses here.

The Victorian reforms did not generate virtues. They did however lead to the emergence of “Victorian virtues” by to some extent restoring the natural conditions necessary for virtue to flourish. Bartholomew does not so much make a philosophical argument that this was the case but he does posit a historical connexion between cause and effect. His thesis is certainly most convincing when he draws parallels with the growth of the welfare state and of moral degeneracy in our own day.

Tribunus is correct in what he writes about Henry VIII and Elizabeth Tudor. The effect of the Reformation on the people of England and Wales was to remove the system of welfare that they had depended for centuries (i.e. the monasteries) and, under Elizabeth Tudor’s government, to make them dependent on the State. The intention of the Elizabethan Poor Laws, however, was surely not to help the poor, or even to “paper over a crack”, so much as to quell a sort of public discontent that could have led to a counter-Reformation. Her father had stolen their religion. Elizabeth Tudor bribed them to give up even its memory. Virtue was no more likely to flourish under this regime than it is under the welfare-state regimes of today.

Far from overlooking these facts, Bartholomew deals with the origins of the English welfare state in the dissolution of the monasteries and the Elizabethan Poor Laws in the second chapter of his book. In fact it is the essence of his historical critique of state welfarism.

Dotheboys Hall is another Dickensian satire. Bartholomew deals with it in his book on page 156.

Dickens seems to have had little interest in morality beyond sentimentality. Even his interst in saving fallen women is at least as questionable as (say) William Gladstone's. Though it has been written here that he was not a "liberal" in the modern sense, Dickens's own ethics were certainly more in line with the populist, permissive values of today rather than with the stern and unbending virtues of his own time.

The same cannot be said of William Hogarth.

There are two situations in which poverty may be a moral issue. Firstly, poverty may be a moral issue if an individual has been deprived of his property unlawfully. There is no indication that this is the case in Hogarth's Gin Lane - though one may perhaps question the ethics of the pawnbroker and the distiller in the picture. Secondly, poverty may be a moral issue if an individual's financial condition is such that it is no longer feasible for him to act morally - if he has to steal for food, for example. Again, this is clearly not the condition of the people in Hogarth's print, who not only have money but are spending it on gin. The gin itself is being purchased rather than stolen, as is clear from the writing in the archway in the bottom left-hand corner. (The writing is not legible in the version provided on this blog. A full-size version of Gin Lane is available here. A Google search will easily provide plenty of others.) The subjects also have the means to make money, because on the left-hand side of the picture they can clearly be seen pawning the tools of their trades in order to buy gin. They are clearly not all paupers.

If Blessed John XXIII had wished to reverse the introduction of the vernacular at Vatican II he could have done so. He did not.

Once again, you fail to read what I wrote.

I did not say he was opposed to all vernacular and wanted to stop it.

I said that he intended Latin to continue to be the normative language of the Church and liturgy.

Moreover, Sacrosanctum Concilium wasn't passed until the Second Period of the Council in Autumn 1963 when Pope John was already dead.

Are you suggesting that he could have come back from the dead to stop the introduction of the vernacular?

Are you suggesting that [Blessed John XXIII] could have come back from the dead to stop the introduction of the vernacular?

This could no doubt be a matter for fruitful theological speculation. In normal circumstances, sadly, a Pope cannot bind his successors. It was then perhaps rash to have written that at VII Blessed John XXIII could have halted the advance of the vernacular in the liturgy had he wanted to. But he didn't want to, and whatever he may have written about Latin ought to be considered in this context.

Of course, Latin is still the normative language of the Church and her liturgy. It's just no longer used very much, and the overwhelming majority of the Roman Catholic clergy can hardly understand a word of it. (Even the JPII Catechism was written in French.)

The fundamental problem with the whole idea of Latin as a language of revelation is that ecclesiastical Latin is to a large extent a made-up language - a sort of Fourth-Century Esperanto - that the Church uses when talking to herself. It's a language of memory, with exact theological definitions that remain unchanged over the centuries precisely because the language is used so little. By the time of the Council of Trent, moreover, it just so happened that St Jerome's version of the Scriptures was the most authoritative still in circulation.

This theological significance of Latin is also to a large extent a red herring in any debate about the liturgy - which is, one suspects, the real agendum behind most of Tribunus' arguments about the language. The purpose of the liturgy certainly is not to "reveal" the Faith, nor is it to hide it. Whether or not the laity can understand the liturgy is, strictly speaking, irrelevant, and it is up to the prudence of pastors whether or not this is even desirable.

But by the same token it is not clear why it should be desirable for the liturgy to be in the same language in all places - except, presumably, as a symbol of the Church's unity. It is hard to shake the feeling that the translation of the scriptures and of the liturgy into an artificial version of Latin (rather than Greek or Hebrew, say) had as much to do with asserting the authority of Rome as it did with making the Faith more widely known and understood - or, for that matter, with the great glory of God in the liturgy.

Moreover it can hardly be doubted that the driving impetus behind the opposition to the Latin Mass, by the Protestant revolutionaries of the Sixteenth-Century outside the Church and by those of the 1960s within, was not any desire to make the Faith more widely understood. Far from it, given that the revolutionaries themselves were and are themselves heretics! Nor was it a wish to make the Liturgy more fitting or pleasing to God. It was simply a rejection (or, in the case of the Popes that went along with it, a surrender) of the authority of the Roman Pontiff.

(Can we not speculate, perhaps with seeming impiety, that the original "Latinisation" of the Mass and the Scriptures was really "Romanisation", under cover of seeming "vernacularism" - and that virtually the same vernacularism has now twice been used, in the Sixteenth Century and four centuries later, as a cover for revolution and dissent?)

*I write 'seeming "vernacularism"' only because for a Greek as much as for a modern Englishman with no Latin there is little to choose between genuine vernacular Latin and the Latin of the Church.

The main effect of the Industrial Revolution was not only urbanisation.

That Cobbett had wanted to restore the pre-Reformation Constitution of England in now way means he opposed progressive legislation. Your logic is faulty.

Cobbett was indeed an Anglican. His interest in Catholicism was clearly genuine, and not purely political, as is clear from his writing. Since his times were hostile to the point of judicial murder, it is ridiculously facile to pretend that his interest was therefore feigned.

You do him an injustice.

For the word 'pauper' The Concise Oxford Dictionary gives '1. a person without means; a beggar. 2. hist. a recipient of poor-law relief'. It was pauperism in this latter sense that the Poor Law reforms of the 1830s was intended to deal.

Your argument on pauperism is simply circular. A pauper is one who receives poor relief and thus poor relief was directed at paupers. Your premise and conclusion are simply identical.

Fatuous.

The poor laws certainly did exploit the poor and often did separate people from their families.

You virtually admit as much when you write: “ Conditions in the workhouses, which had already been in existence for a long time, were deliberately made harsher in order to discourage dependency”.

They were not harsh but then again they were harsh. Well? Which is it?

And to say that paupers “were not forced into the workhouses” is a comment of such inter-galactic cynicism I am surprised you dare t make it. Poverty forced them! You know this. To say that they were free to take up paid employment whenever they wished, unemployment levels notwithstanding, is another comment of polished cynicism.

You are in danger of dwelling in a neo-Thatcherist economic libertarian fantasy world of your own making. Come back to earth.

Your later comments on the Elizabethan poor laws does not contradict mine but rather concur.

Lastly, you seem to think that satire cannot reflect reality. The reverse is true.

The main effect of the Industrial Revolution was not only urbanisation.

That Cobbett had wanted to restore the pre-Reformation Constitution of England in now way means he opposed progressive legislation. Your logic is faulty.

Cobbett was indeed an Anglican. His interest in Catholicism was clearly genuine, and not purely political, as is clear from his writing. Since his times were hostile to the point of judicial murder, it is ridiculously facile to pretend that his interest was therefore feigned.

You do him an injustice.

For the word 'pauper' The Concise Oxford Dictionary gives '1. a person without means; a beggar. 2. hist. a recipient of poor-law relief'. It was pauperism in this latter sense that the Poor Law reforms of the 1830s was intended to deal.

Your argument on pauperism is simply circular. A pauper is one who receives poor relief and thus poor relief was directed at paupers. Your premise and conclusion are simply identical.

Fatuous.

The poor laws certainly did exploit the poor and often did separate people from their families.

You virtually admit as much when you write: “ Conditions in the workhouses, which had already been in existence for a long time, were deliberately made harsher in order to discourage dependency”.

They were not harsh but then again they were harsh. Well? Which is it?

And to say that paupers “were not forced into the workhouses” is a comment of such inter-galactic cynicism I am surprised you dare t make it. Poverty forced them! You know this. To say that they were free to take up paid employment whenever they wished, unemployment levels notwithstanding, is another comment of polished cynicism.

You are in danger of dwelling in a neo-Thatcherist economic libertarian fantasy world of your own making. Come back to earth.

Your later comments on the Elizabethan poor laws does not contradict mine but rather concur.

Lastly, you seem to think that satire cannot reflect reality. The reverse is true.

Your comments on Hogarth’s Gin Lane do not detract from my point at all. Indeed, they lend support to what I said.

You concede my point about Pope John XXIII and then focus on the separate issue as to whether or not Latin is a language of revelation and go n to make the same errors you before made.

Ecclesiastical Latin of the 4th century was certainly no Esperanto, whatever you may say.

You then confuse vernacular use of the language with its use as a vehicle of revelation and compound the error by claiming it was relevant because St Jerome’s Bible “just happened” to be the most authoritative, as if it were all some huge accident.

Even more fatuous is the claim that Latin is a “red herring” in the debate on liturgy and one beigns to wonder what planet Glorfindel has been a-wandering upon these last 40 years.

Liturgy is certainly a means of revealing faith but the sense in which Latin is a language of revelation is not so much in that sense, which is a different use of the term “revelation”, but in the fact that the definitive and infallible teaching of the Catholic Church - i.e. when we may be most sure that the Holy Ghost is speaking and revealing to the whole Church – is invariably rendered in Latin.

It is in that sense that it may be said that Latin is a language of revelation.

You are, in any case, wrong about liturgical language if you think that Latin is the only such language (as you seem to think with your ahistorical talk of Rome asserting its authority by imposing the language than which nothing could be further from the truth).

There are 22 different rites of mass in the Church and the other languages of revelation are as much authentically liturgical languages as ever.

Greek is the official liturgical language of the Melchite, Maronite and Greek rites; Aramaic (Hebrew) of the Chaldean , Syrian and Syro-Malabarian and Syro-Malankarian rites.

Other languages are not ruled out, provided they are liturgical and for a good reason e.g. the Old Slavonic of the Russian and Ukrainian rites and Glagolitic in the Croatian rite.

You are, however, to some extent right, I suggest, to say that opposition to Latin “was simply a rejection (or, in the case of the Popes that went along with it, a surrender) of the authority of the Roman Pontiff”.

My main point, however, remains. The reasons for the use of Latin, Greek and Hebrew in the liturgy are not primarily to do with vernacularisation but rather to do with preserving the language of revelations for the transmission of the sacred whether in law, in liturgy, in theology or in revelation.

You concede my point about Pope John XXIII and then focus on the separate issue as to whether or not Latin is a language of revelation and go n to make the same errors you before made.

Ecclesiastical Latin of the 4th century was certainly no Esperanto, whatever you may say.

You then confuse vernacular use of the language with its use as a vehicle of revelation and compound the error by claiming it was relevant because St Jerome’s Bible “just happened” to be the most authoritative, as if it were all some huge accident.

Even more fatuous is the claim that Latin is a “red herring” in the debate on liturgy and one begins to wonder what planet Glorfindel has been a-wandering upon these last 40 years.

Liturgy is certainly a means of revealing faith but the sense in which Latin is a language of revelation is not so much in that sense, which is a different use of the term “revelation”, but in the fact that the definitive and infallible teaching of the Catholic Church - i.e. when we may be most sure that the Holy Ghost is speaking and revealing to the whole Church – is invariably rendered in Latin.

It is in that sense that it may be said that Latin is a language of revelation.

You are, in any case, wrong about liturgical language if you think that Latin is the only such language (as you seem to think with your ahistorical talk of Rome asserting its authority by imposing the language than which nothing could be further from the truth).

There are 22 different rites of mass in the Church and the other languages of revelation are as much authentically liturgical languages as ever.

Greek is the official liturgical language of the Melchite, Maronite and Greek rites; Aramaic (Hebrew) of the Chaldean , Syrian and Syro-Malabarian and Syro-Malankarian rites.

Other languages are not ruled out, provided they are liturgical and for a good reason e.g. the Old Slavonic of the Russian and Ukrainian rites and Glagolitic in the Croatian rite.

You are, however, to some extent right, I suggest, to say that opposition to Latin “was simply a rejection (or, in the case of the Popes that went along with it, a surrender) of the authority of the Roman Pontiff”.

My main point, however, remains. The reasons for the use of Latin, Greek and Hebrew in the liturgy are not primarily to do with vernacularisation but rather to do with preserving the language of revelations for the transmission of the sacred whether in law, in liturgy, in theology or in revelation.

Post a Comment